They are back!

They are back!

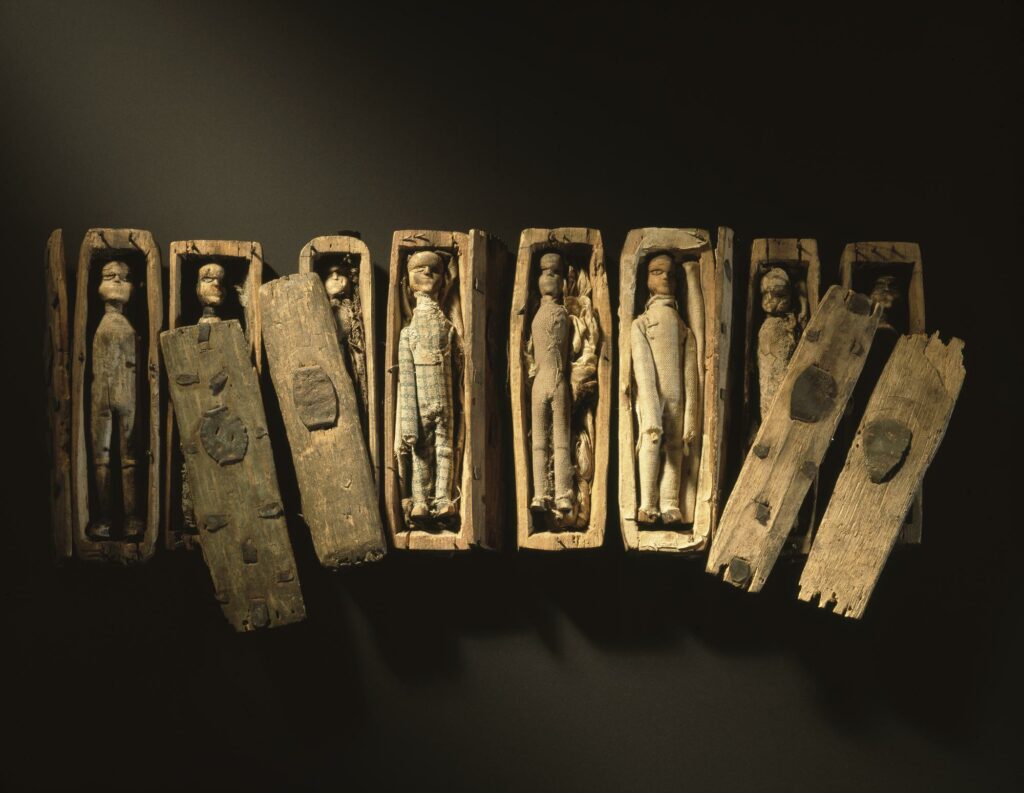

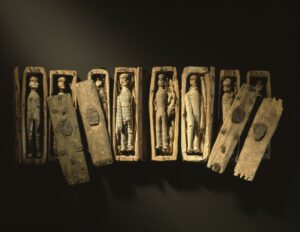

After four months in the recent National Museum of Scotland’s paying exhibition, ‘Anatomy A matter of Death and Life’, the Arthur Seat’s coffins are back on free display in the Scotland Galleries of the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) in Chambers Street (section ‘Daith comes in’ of ‘Scotland Transformed’ on level 4). They are eight little wooden coffins each containing a clothed wooden male figure which were found in June 1836 (along with nine others that have apparently not survived) in a cavity on the north-eastern side of Arthur’s Seat. They are among the three most popular items in the NMS to which visitors ask directions. Given the seclusion of their location, I can say from experience that they are easily the most complex directions to give.

These miniature coffins intrigued the author Ian Rankin who used them in his crime novel, The Falls (2001, pictured below right). This possibly accounts for some of their popularity. The book was made into a film for TV in 2006 and the replicas made for filming stood in for the originals whilst they were in the special exhibition. When they are not standing in for their illustrious originals the replicas are to be found in ‘Scotland, a Changing Nation’ in the Scottish Galleries on level 6, where Ian Rankin’s comments on the coffins can also be seen.

Since they were found they have prompted the question, who or what do they represent and why were they hidden on Arthur’s Seat? The most convincing explanation was put forward by Samuel Pyeatt Menafee and the late Allen D C Simpson in their article, ‘The West Port Murders and the Miniature Coffins from Arthur’s Seat’, in the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, New Series volume 3, pp 63-81 (1994). Briefly, the figures probably represent the victims of the serial murderers, Burke and Hare. According to Owen Dudley Edwards in his book, Burke and Hare, they can be regarded as classic entrepreneurs who having identified a gap in a market proceeded to fill it, to their pecuniary advantage. It can be argued that the market in question was indirectly created by the Act of Union of 1707. With the departure of Scottish legislators and the paraphernalia of government south to London the City Fathers sought to bolster Edinburgh’s economy by founding not a Festival but a medical school in ‘The Toonis College’. Whilst this raised the City’s profile there was an unintended consequence.

Since they were found they have prompted the question, who or what do they represent and why were they hidden on Arthur’s Seat? The most convincing explanation was put forward by Samuel Pyeatt Menafee and the late Allen D C Simpson in their article, ‘The West Port Murders and the Miniature Coffins from Arthur’s Seat’, in the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, New Series volume 3, pp 63-81 (1994). Briefly, the figures probably represent the victims of the serial murderers, Burke and Hare. According to Owen Dudley Edwards in his book, Burke and Hare, they can be regarded as classic entrepreneurs who having identified a gap in a market proceeded to fill it, to their pecuniary advantage. It can be argued that the market in question was indirectly created by the Act of Union of 1707. With the departure of Scottish legislators and the paraphernalia of government south to London the City Fathers sought to bolster Edinburgh’s economy by founding not a Festival but a medical school in ‘The Toonis College’. Whilst this raised the City’s profile there was an unintended consequence.

In those days, a medical student would have to dissect something between three and five cadavers during their course. Given a couple of hundred students a year there was a need for anything up to a thousand bodies a year for dissection. There was no legal way to obtain bodies other than those of criminals executed for murder. As the total number of executions in Edinburgh for murder tended to be in the low single figures each year a mismatch between supply and demand existed.

There therefore grew up an unofficial trade whereby recently filled graves were robbed to provide a sufficient supply of cadavers. A blind eye tended to be turned by the authorities as the reasonably well-to-do could afford to take measures to prevent the bodies of their nearest and dearest ending up in the dissecting rooms and those who could not had little political influence. Steps were only taken against ‘grave robbers’, ‘body snatchers’, ‘sack-‘em-up men’, or ‘resurrectionists’ , call them what you will, when their activities alarmed the populace so much that public order was likely to be disturbed. Even if grave robbers were caught, the punishment for the crime of ‘violation of a sepulchre’ was six months in gaol. In law no one can own a body so legally it cannot be stolen. If, however, they also stole the shroud – which is property – they could be hanged for theft.

Although Burke and Hare are commonly referred to as ‘grave robbers,’ there is no evidence that they actually ever set spade to recently filled graves. Their first subject was an old man who died of natural causes in Hare’s lodging house owing him a quarter’s rent. Burke and Hare replaced the body in the coffin with tanner’s bark before the funeral. They then sold the body to Dr Knox’s private anatomy school thus more than recouping Hare’s lost rent.

Although Burke and Hare are commonly referred to as ‘grave robbers,’ there is no evidence that they actually ever set spade to recently filled graves. Their first subject was an old man who died of natural causes in Hare’s lodging house owing him a quarter’s rent. Burke and Hare replaced the body in the coffin with tanner’s bark before the funeral. They then sold the body to Dr Knox’s private anatomy school thus more than recouping Hare’s lost rent.

Their innovation in the supply of bodies for dissection was not to wait for the subject to die from natural causes but to render them blind drunk with whisky and then suffocate (or ‘burke’) them. Despite their activities, the furore that resulted from their discovery, and the execution of William Burke in 1829 it took another three years and the discovery of the adoption of Burke and Hare’s business model by Messrs Bishop, Williams and May in London for the Anatomy Act of 1832 to be passed. This allowed the unclaimed bodies of paupers who had died in workhouses to be ‘anatomised’, thus ending the resurrection trade.

In case you are wondering, the other two most sought objects in the Museum are the Lewis Chessmen and Dolly the Sheep, neither of which has (yet) featured in an article in the BOEC.

By Ted Duvall, President, Old Edinburgh Club