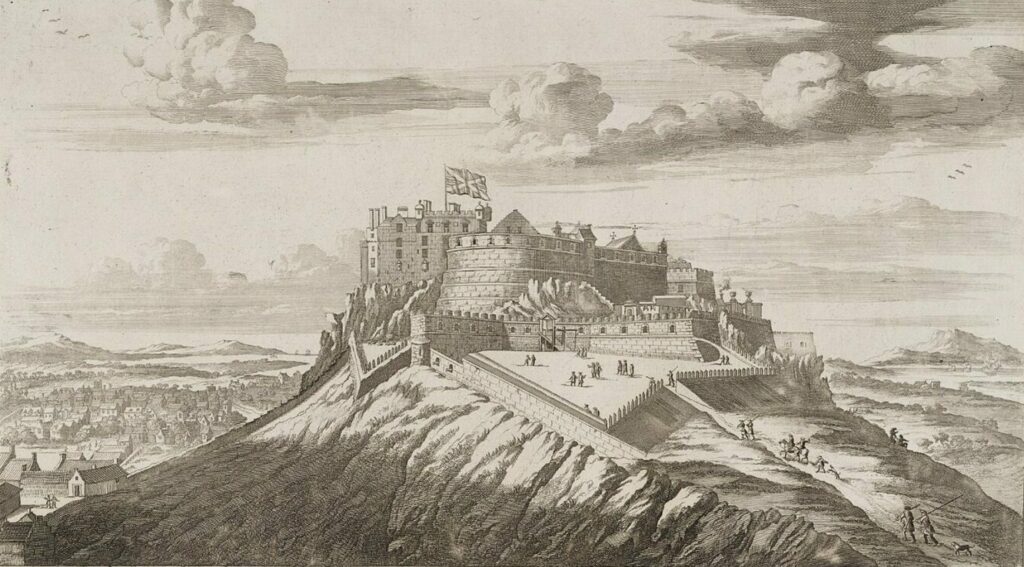

Pickets, Bombardments and Spies: The Siege of Edinburgh Castle (18th March-15th June 1689)

On a brisk and clear night, 25th March 1689, a soldier stood sentry upon the western ramparts of Edinburgh Castle. Witnessing some peculiar flashes in the darkness below he alerted his comrades and before long the Governor of the Castle, George Gordon, first Duke of Gordon, had been summoned. Gordon quickly determined that these were not the candles of residences or the torches of wayward travellers. These flashes were ‘squibs’, small explosive charges often used in mining. The men utilising them were a party of soldiers and engineers moving earth for trenches. Inadvertently, the flashes had revealed their positions and Gordon ordered a battery of cannons to fire upon them. This halted the work and destroyed what had already been accomplished.

This was but one event in the Siege of Edinburgh Castle, which lasted from 18th March 1689 until 15th June 1689. The siege remains little known outwith academic circles, yet this obscure battle was the first in a nationally significant civil war and the first battle of the Jacobite Risings. The Highland War, often better known as the First Jacobite Rising, only lasted three years (1689-1691) but would prove to be a divisive and bloody conflict.

This article reveals how this little-known siege impacted the City of Edinburgh and, indeed, Scotland in 1689. It uses contemporary sources, uncovered in doctoral research, to explore not only the military contours of the siege but to highlight the experiences of those involved, soldiers and civilians, as they sought to navigate, and, in some instances, influence this tumultuous moment in Scottish history. Before relating the siege itself, we must understand the events which led to this eruption of violence on the streets of Scotland’s capital.

Backdrop to the Siege

On 5th November 1688, a Dutch army of 14,000 professional soldiers, augmented by British exiles, landed in England. They were led by Prince Willem Hendrik of Orange, soon-to-be William II & III. This army sought to remove, or at the very least contain, the power of King James VII & II. The geo-political causes of the so-called ‘Glorious’ Revolution in England are well known. The violent impact that this constitutional and dynastic shift had upon Scotland remains less so.

The election and meeting of a Scottish constitutional meeting, the Convention of Estates, occurred against a background of sporadic religious and political violence. The Scottish Estates had been convened to resolve the political vacuum caused by the exile of James and the installation of William as caretaker of his realms, Scotland, England, and Ireland – the Three Kingdoms. First meeting on 13th March 1689, matters began to escalate with the return of King James to Ireland, where he was met by a large Catholic army. James’s Scottish supporters, the Jacobites, sought to support his return and denounced William as a ‘usurper’. On the other hand, William’s supporters, the Williamites, argued that James had acted tyrannically and that James’s departure left the throne vacant. The disbandment of the Scottish standing army in December 1688 had left only a handful of regular soldiers, mostly men in garrisons like Edinburgh Castle. Unable to exert military control, the Jacobites found themselves swiftly outmanoeuvred in the Convention and the Williamites gained de jure control of the country. Their intention to depose ‘the Late King’ and put William, and his wife Mary, in his place incensed the most militant Jacobites, led by John Graham, first Viscount Dundee. Gordon steadfastly refused to surrender control of the Castle to the Convention. The Convention believed this to signal his support for James and forbade anyone from communicating with him on pain of treason. On 18th March 1689, Viscount Dundee withdrew from the Convention and would subsequently raise the first Jacobite army in the Highlands. Before departing, the Viscount ascended Castle Hill and briefly spoke with Gordon, reportedly exhorting him to stand firm and promising to return. This sparked a major panic among the Williamites and led them to the mobilisation of local militias across the country. This marked the beginning of the Highland War.

The Siege begins

The first shots in this new conflict rang out on the streets of the capital as armed volunteers, mostly Lowland Presbyterians from the ‘Western Shires’, traded ragged musket volleys with the garrison. Gordon and his men had prepared for this eventuality but an anonymous member of the garrison, writing a later account of the Siege, noted that they only had a fifth of the three-month supply of food and drink they had sought before James’s government collapsed. Gunpowder, shot, and cannon balls were also severely lacking. There were 127 men, including officers, serving in the garrison and they were augmented by a small group of Jacobite ‘gentlemen voluntiers’ led by Francis Gairdin [Gardyne] of Midstrath. These men slipped into the castle, accompanied by eighteen women, to support Gordon on 16th March. Initially, they were encircled by 6-7,000 Presbyterian volunteers, referred to as the ‘Cameronian Guard’ named for the late Covenanting field preacher Richard Cameron. The ‘Guard’, however, were militarily inexperienced and- largely ineffectual. The newspaper, Proceedings of the Convention of Estates, reported ‘The Guards that block up the Castle and the Garison in it, fire one at the other with Small shot; little harm is as yet done; few on both sides wounded, none killed’. There were intermittent ceasefires during the first week or so as the sides negotiated unsuccessfully. Some of the soldiers on either side would pass the time in trading insults across the lines. The anonymous member of the garrison noted that many of the Highlanders, on both sides, spoke to one another in Gaelic and some of these men among the Williamites seemed sympathetic to the Jacobite cause. This placid state of affairs changed drastically when regiments of professional soldiers, dispatched north by William of Orange, arrived.

The main body of these was the Scots-Dutch Brigade, an elite formation of Scottish troops loyal to the Dutch Republic and William of Orange. These veterans of European warfare swiftly began putting their expertise to use along with the cannons and mortars they brought from London. With permission from the Convention, the Brigade began digging new artillery emplacements at ‘Collups Castle’ (an old ruined tower at the corner of the Flodden Wall), George Heriot’s School and at ‘Mouter House Hill’ (or Moutrie Hill, now St James Square) . The Scots-Dutch officers also erected a circumvallation – ‘a trench to be made about that part of the Castle… which lies toward the country, to hinder communication of intelligence and provisions, with the Duke of Gordon’. Their commander, Major-General Hugh Mackay, requisitioned packs of wool from agitated local merchants to create make-shift fascines (screens) to block cannon fire from the Castle. They used these to shield teams of soldiers and engineers who began digging trenches toward the walls which would better facilitate a direct assault. All of these efforts were, however, costly for the Williamites as they completed each battery under fire and, as the Jacobite writer notes, ‘with the losse of men’. Only the west battery, near Heriot’s, had any success in creating a breach but the notion of a direct Williamite assault was swiftly abandoned in favour of continued encirclement and bombardment.

Disruption of Edinburgh residents

The Siege of Edinburgh was, then, becoming more and more disruptive to the people of Edinburgh. Mr James Nimmo, a diarist living in the Grassmarket with his wife, wrote ‘we could hardlie go out or in, but in vew [sic] of the Castle & they [the Jacobites] haveing killed some persons upon the streat, freinds wer verie pressing for our removing from thence’. By 18th April, the Proceedings reported ‘Mackay’s men, and the Castle, fire fiercely one at the other; this day more Cannon, Mortarpieces [sic], Bombs, &c are arriv’d from London, so that speedily there will be smart work betwixt them’. Many inhabitants of the burgh were less enthusiastic than James Barclay with several later petitioning the Council for compensation for damage to their seized properties and loss of goods. Thomas Campbell, a deacon of the Fleshers, had many of his tenants in the Westport uprooted as ‘his Majesties forces did sumer last raise a battaire’. The house which he rented ‘being so near the batterie… was demolished’. Another, Thomas Johnstone, a tenant of the said house, was forced to move whilst he was ill. All sorts of ‘ware… and liquors’ was lost during the siege. Many received such short notice to vacate, usually less than a night, from Major-General Mackay and his second-in-command, Major John Sommerville. Economic disruption became a major issue as ‘the ordinary Road to the Markets by the Castle-Wall’ became too dangerous for goods to travel and the small market gardeners were unable to tend their crops. The entire trade of the Grassmarket seems to have been relocated for the duration of the siege.

Local support

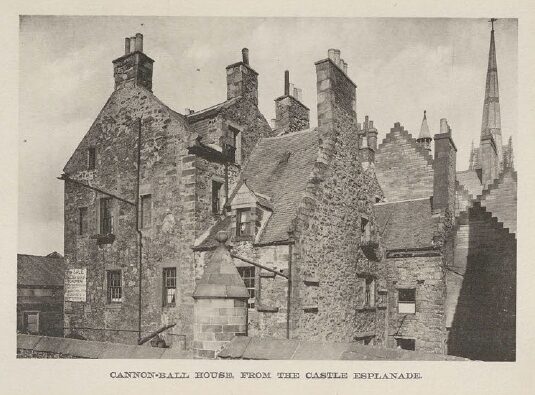

Although the Jacobites found themselves outnumbered, under supplied and outgunned, they had an oft-overlooked group of allies; sympathetic civilians. Sir James Grant of Davey, a baronet and advocate, and John Gordon of Edintore sought to organise supplies for the beleaguered garrison. Others also participated in relief efforts. These clandestine networks did, however, have success in delivering Jacobite correspondence from Ireland. Letters from within the Gordon family’s collection reveal that King James wrote twice to Gordon during the siege, with the letters dated 25th March and 17th May respectively. Even more ingenious was the signalling system devised by Miss Ann Smith, granddaughter of Dr James Atkins, Bishop of Galloway. Smith lived in the ‘upper-most’ house on Castle Hill, just beneath the imposing walls, and used the position of her lodgings to communicate with Gordon. Instead of risking passing letters directly into the garrison, she wrote headlines of events in large capital letters on a table and then pushed the table toward a window where Gordon could read the news via telescope. When she was unable to do this, she began hanging out cloths to signal the nature of the news, a white cloth for good or a black cloth for bad. Others used more risky means. Lilias Aitken, her husband Patrick Smith, their daughter and Isobell Farquarson, were apprehended for passing intelligence and supplies to the Castle via the low gate. This group was arrested after the so-called ‘Faithless Fifteen’ deserted the garrison and betrayed the network in exchange for pardon from the Williamite regime.

The endgame

By 12th June 1689, many of Gordon’s men were injured, sickly and starving. The garrison was bereft of drinking water and was running on almost no food. He called for a ceasefire and parley with Major-General John Lanier, Lieutenant-Colonel James Mackay and Major Sommerville. On 13th, the Williamite officers presented Gordon with articles for his surrender, but the meeting was disrupted when a messenger bolted past the group and into the Castle. The Williamites were incensed and demanded the garrison surrender the man immediately. The ceasefire broke down almost as quickly as it had been called and a penultimate barrage erupted. ‘The Treaty being ended, the Garison fired both their great and small Shot all that Night against the Town it self, and every way that they thought to do mischief, several persons being killed, others wounded, and some Houses prejudiced by the Cannon’. On the morning of 15th June 1689, Gordon and his men agreed to the articles of surrender and the Jacobite garrison marched out to Castle Hill where they laid down their arms and three hundred Scots-Dutch soldiers marched into the castle under the colours of their regiment. The anonymous Jacobite notes that Gordon secured good terms for his men as he surrendered himself to the Williamites in exchange for their release. Three full months after the siege began, the garrison marched out ‘but not in a body, that they might be the less noticed’.

The Siege's place in history

The 1689 Siege of Edinburgh Castle is a little-known yet fascinating episode in Scotland’s early modern history and a pivotal moment in the Highland War. Although the siege was relatively modest in scale, its military significance cannot be understated. The nascent Williamite regime had to fight to gain control of Scotland’s premier fortification and for the first three months of its existence it remained under threat from the Jacobite garrison. Moreover, the siege highlights to us that the First Jacobite Uprising was not a minor insurrection contained in the ‘remote’ Highlands but a national civil war. The experiences of the inhabitants of and, indeed, participants in the Siege of Edinburgh (18th March to 15th June 1689) underline that fact.

About the author, Graeme Millen

Dr Graeme S. Millen is a part-time tutor at the University of Dundee and a part-time policy analyst. He completed his PhD at the University of Kent, entitled ‘The Scots-Dutch Brigade and the Highland War, 1689-1691’, in 2022. He has published a chapter on ‘The Scots-Dutch Moment? The Scots-Dutch Brigade and the Highland War, 1689-1691’ as part of Brill’s recently released Monarchy, the Court, and the Provincial Elite in Early Modern Europe. Last year he published a four-part series on the Highland War in History Scotland magazine.

Further reading

Readers interested in discovering more about the Siege, please refer to ‘Pourtrait of True Loyalty’ by an unknown author writing at the time, and later published by the Bannatyne Club in 1828. Extracts were published in the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club in 1928 (Original Series Volume 16, pp. 171-213), which can be downloaded here.